Published online 9/26/25 and in The Falmouth Enterprise’s Friday edition, pages 1 & 12. Written by Katie Nelson. A number of FHMNA Directors and members attended this online video conference.

During a virtual site visit and consultation session held Monday, September 22, Falmouth Wastewater Superintendent Amy A. Lowell outlined key details of the town’s proposed ocean outfall project, explaining its necessity to reduce nitrogen pollution in local waterways and accommodate expanded sewer capacity.

The event was held to gather advice and comments from agencies, officials and residents regarding which environmental issues, if any, are significant for this project and included a presentation on completed and upcoming environmental studies and a discussion of the project’s Environmental Notification Form (ENF), which the town is seeking from the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA).

Alexander Strysky, an environmental analyst from the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) office, opened the meeting. He said the session was informal and not a public hearing. Public comments are being accepted until Tuesday, September 30, Strysky said. Those who wish to provide a comment on environmental issues related to the outfall project can email Strysky questions and comments or they can be submitted via the officer’s public comment portal.

Representatives and officials from regulatory agencies like the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), as well as members of the Water Quality Management Committee and the Falmouth Heights Neighborhood Association, all attended the virtual meeting.

Lowell began her presentation by explaining why the outfall is necessary. The town is mandated by MassDEP to reduce nutrient loading, primarily of nitrogen. Excess nitrogen from septic systems, stormwater runoff and fertilizers can and have impaired Falmouth waterbodies. Nitrogen loading into waterbodies causes eutrophication, which leads to algal blooms and decreased water quality and overall health of ponds and coastal embayments. Falmouth has 14 MassDEP-designated, nitrogen-impaired coastal ponds and embayments. The state requires the town to reduce its nitrogen loading to a total maximum daily load of 10 mg/L.

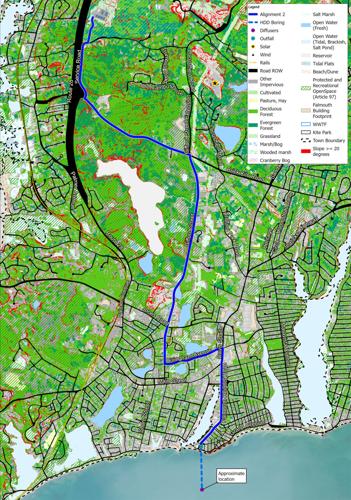

To reduce nitrogen loading, the town is moving forward with a sewer expansion in the Great Pond Phase One sewer project, which will connect the northeastern section of the Maravista Peninsula and the Teaticket peninsula to town sewer, Lowell said.

As the sewer expands, the town’s wastewater treatment plant will require a larger capacity for treated wastewater discharge, Lowell said. The town currently discharges treated water into sand beds at the wastewater treatment plant.

The ocean outfall will bring tertiarily treated wastewater from the wastewater treatment plant to 2,300 feet offshore from Kite Park in Falmouth Heights, into Nantucket Sound. The end of the outfall pipe will be beyond eelgrass marine habitats, she said. The six-mile pipe will be made of high-density polyethylene, which is flexible and has no joints.

When the outfall is in place, Lowell said the wastewater treatment plant will stop discharging to the sand beds and will only use the sand beds as a backup in cases of maintenance or repair.

Lowell said Falmouth’s ocean outfall will differ from existing outfalls in the state in a few ways.

The water traveling through the outfall will be treated three times and disinfected with ultraviolet light. Historically, Lowell said, outfalls have discharged water that has only been treated once or twice.

Also, the town does not and will not have combined sewers, Lowell said. That means, the town will not have any bypass events in the event of a storm. Bypass events in combined sewers temporarily divert wastewater in the event a sewer becomes overwhelmed, caused by heavy rain or storm conditions. Lowell said many older outfalls do have combined sewers and bypass events, which could result in sewer overflows, but Falmouth’s sewer system will not. In the event of a sewer emergency or a failure that would require repairs, Lowell said, valves along the six-mile outfall would be engaged to stop the flow. Lowell said the process is similar to how water mains are controlled. She said the flow could be temporarily discharged to the sand beds at the wastewater treatment plant while repairs are made.

Lowell also noted the tidal velocity in Nantucket Sound is faster than at any other outfall location in Massachusetts. The speed of tidal velocity is important to avoid any potential nutrient loading at the outfall site. If the water is moving quickly, the speed at which the treated water is disbursed and diluted will lessen the likelihood of nitrogen concentrations. Lowell said the end of the outfall will also have diffusers that will propel the treated water into the ocean, ensuring that the treated water will go outward, into Nantucket Sound, and no water, either the treated water or ocean water, will enter the pipe.

Following her presentation, Lowell took questions from the audience.

Resident Ralph D. Walkowicz asked Lowell why Buzzards Bay is not considered a suitable site for the outfall, given its proximity to the wastewater treatment plant. Lowell, again, highlighted the importance of tidal velocity and how that factored into the deamination of Nantucket Sound for the outfall location. The tidal velocities in Buzzards Bay are “a fraction of what they are in Nantucket Sound,” Lowell said. Because the water is moving more slowly, Lowell said an outfall would have to go further offshore in Buzzards Bay to make sure the water being discharged is diluted quickly, thus making the physical outfall pipe longer, and therefore, more expensive.

Resident Mari T. Walkowicz said she is concerned about Falmouth Heights Beach and machinery staged at Kite Park. She asked if it will be available for recreational use by the summer months. Walkowicz also asked if the outfall would cut through the boulders, which hold up the bluffs at the Heights.

Lowell said all directional drilling for the project will take place in the offseason in the fall and winter, so summer recreation will not be interrupted. The outfall pipe will run through town from the treatment plant and under Kite Park, the bluffs and the beds of eelgrass. Lowell also said that the final layout of Kite Park, which will be used as a staging area, has not been decided yet. However, the park will be fully restored to preconstruction conditions when construction is complete.

Strysky asked Lowell if any additional pump stations would need to be installed to propel the treated water through the outfall. Lowell said a final determination on a pumping station has not yet been made. But, she said, if it is determined to be required, the pumping station will likely be located at the wastewater treatment plant. She said there are no pump stations currently planned, but if the outfall flow exceeds what is expected in the next 10 to 15 years, a pumping station may be required.

Lealdon Langley of MassDEP asked Lowell if there had been consideration to continue to discharge tertiarily treated water to the existing sand beds at the wastewater treatment plant. Lowell gave a brief history of the wastewater treatment plant to explain why discharging to the sand beds is not desirable. When the plant was first built in the 1980s, Lowell said roughly 20 years of “not very well-treated water” was discharged there. As a result, West Falmouth Harbor, which is downhill and to the west of the treatment plant has a legacy plume of nitrogen, which has impaired water quality in the harbor.

In 2005, the wastewater treatment plant added a third step to its treatment process to increase its effectiveness. Lowell said the treatment processes at the wastewater treatment plant remove approximately 94% of the nitrogen in the water, but 6% still remains.

“Even though we’re treating the water well, we’re still importing nitrogen into West Falmouth Harbor,” Lowell said.

“The primary limiting factor everywhere is nitrogen,” Lowell added. Discharging the water into the groundwater anywhere in Falmouth, risks the health of an already nitrogen-impaired coastal pond or embayment, she said.

The town hopes the state will certify the ENF by Friday, October 10. After that, a draft environmental impact report will be prepared, which the public will also be able to comment on.